Posts Tagged intervention

Designing Intervention for Between-Language Transfer

Posted by Elizabeth D. Peña in between-language, bilingual, developmental language disorder, intervention on January 4, 2022

SLPs working with bilingual children often ask how to design interventions that promote transfer. We know that it’s not appropriate to take away a child’s home language. We also know that most SLPs (95% or more) only speak one language. So what do we do?

This is a question that my colleagues and I have thought about a lot. I’ve written about our previous studies here and here. We know that not everything transfers. Some parts of language seem to more readily transfer between languages. Usually meaning including story structure, vocabulary and semantics. But form doesn’t transfer as easily. If forms are shared– plural s in Spanish and English for example, they are more likely to transfer. But, it’s less likely that the subjunctive form in Spanish will transfer to English. They are too different.

Still, we wanted to incorporate grammatical goals into our intervention since grammar is an area of difficulty for children with DLD. First, we thought about broad principles of language learning that would support transfer. We drew from MacWhinney’s Unified Model to help us think about transfer:

- Resonance helps to reinforce patterns. We made sure that the vocabulary we used was drawn from the curriculum, and that we used the vocabulary in full phrases and sentences. We reasoned that this would help children learn the grammatical patterns as well as the vocabulary.

- Proceduralization helps children make connections. Rather than teaching grammatical forms in isolation we emphasized features in larger story telling contexts using repeated exposures.

- Internalization is the process by which children may regulate their own actions through language. We expand this by supporting children’s use of L1 in supporting metalinguistic awareness. We propose that this self-talk in the L1 can help form a bridge between L1 and L2 learning.

- Transfer can be negative or positive. In negative transfer, children might incorrectly apply patterns for their L1 to the L2. In positive transfer they might use what they know to leverage use of forms in L2. We tried to promote positive transfer through use of cognates, and through pointing out similarities (and differences) in the grammars of the two languages.

Grammatical Target Selection

In our study, we did not individualize targets for each child. Instead, we identified the kinds of targets that are most difficult for children with DLD in Spanish and in English. We wanted to provide support for grammatical comprehension and production within narrative and expository texts. What’s seems to be difficult for children with DLD is forms that are less salient in the input. We identified constructions at a broad level that are difficult for children with DLD in both Spanish and English and also how they might manifest differently across the two languages. We thought about effective communication through elaboration and precision. Targets we chose included the following:

- Elaborated noun phrases are the building blocks for grammar across both languages. And we could build up the vocabulary words they were learning into these descriptive phases. We included use of prepositions and adjectives. In Spanish, we made sure to focus on number and gender agreement in using adjectives + nouns since this is an area of difficulty for kids with DLD.

- Tense and complex utterances were targeted to help support expression of causal and temporal relationships within the stories that children hear, read, and told.

- Deictic reference – we incorporated use of articles and pronouns from the texts to emphasize different points of view, references, and agreement.

Results indicated significant gains across grammatical forms in Spanish including (clitics, subjunctive, imperfect, and adjective agreement). There were also significant gains in English (even though the intervention was completely in Spanish). Gains we noted in English included 3rd singular, passives, and negatives. We think that through an approach which emphasized expression of complete and elaborated ideas, children started paying more attention to ways they could be more precise in their use of grammar. Thus, in this study, it wasn’t about the specific forms but rather providing the tools (and models) that children could use to express their knowledge through language. The focus wasn’t as much on the “correctness” of use but on elaboration and expression of meaning. And this could be done across both languages.

This is just a small study, but it gives us a glimpse into how we can use these learning principles with broad grammatical targets to support transfer. If you want to read the original paper, you can do so here.

Bilingual Research Needs

Posted by Elizabeth D. Peña in assessment, bilingual, bilingualism, child bilingualism, child language impairment, Uncategorized on August 19, 2016

I’m at the airport in Washington DC after participating in a workshop at tha NIH on dual language learners. We talked about the state of the art. What’s cool is that there has been so much progress. We know that bilingualism isn’t bad for you and that in fact it could be good for you. We have better ideas about how to diagnose bilinguals with language impairment. At least in some languages. We know about what works for Spanish and English. We have emerging data for Mandarin-English and Vietnamese-English as well as other language pairs. We have an emerging picture about bilingual development in two languages.

But, there’s still a lot we don’t know. We don’t fully understand how changes in the linguistic environment affect child performance on language measures. We still don’t have a God handle in intervention for bilinguals with langquge impairment. Do we treat in one language or both? Do we use translanguaging approaches?

I don’t think we fully understand how bilingualism affects the brain. Nor do we know how the environment shapes the brains of children with language impairment.

We heard about reading disorder and mechanisms associated with dyslexia. Children can and do learn to read in two languages but we don’t really understand how those languages interact and how languages that have different writing systems interact in the bilingual brain.

Even though we’ve made progress in identification of impairment we don’t do such a great job across languages and at all ages.

So we know a lot we have a ways to go

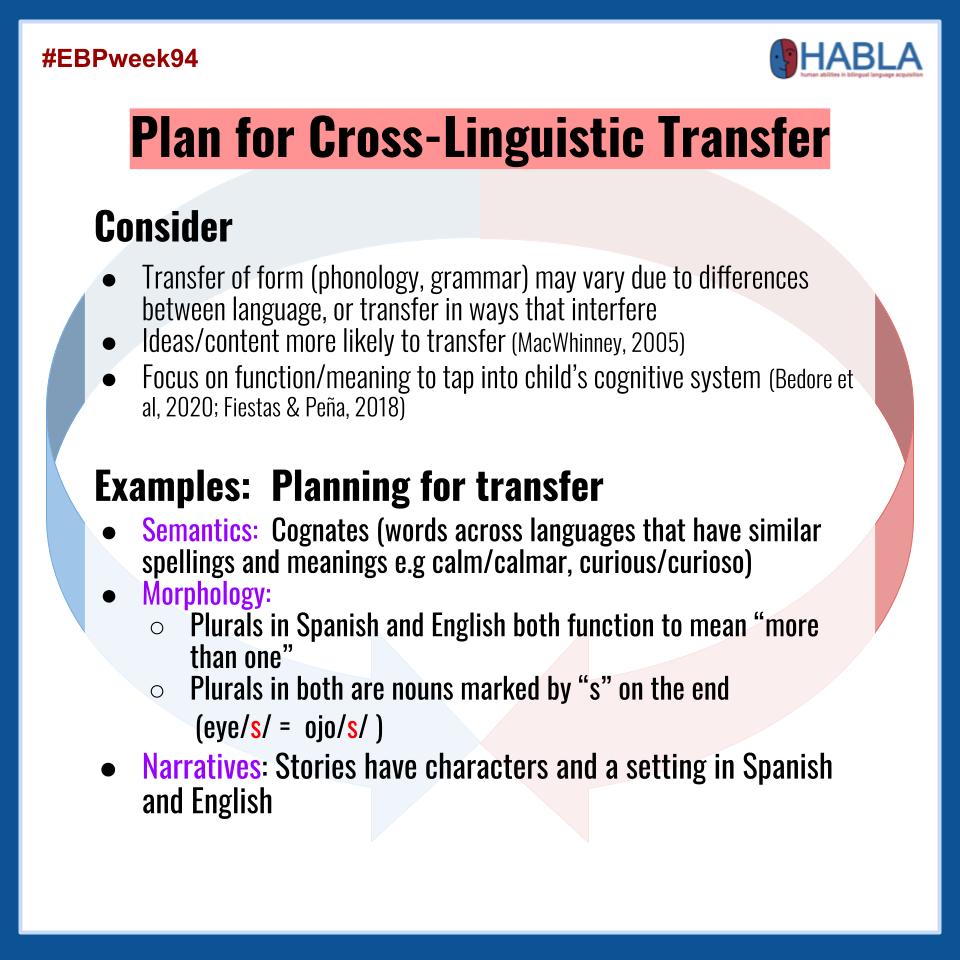

Planning for between-language transfer

Posted by Elizabeth D. Peña in between-language, child bilingualism, grammar, morphosyntax, narratives, semantics, vocabulary on May 29, 2015

I don’t think that transfer (between languages) just happens. I think you have to plan for it. So, what kind of things transfer? How can we use what we know about language transfer to maximize transfer between two languages? Last time I talked a little about a study we had recently published in Seminars in Speech and Language s (I encourage you to read the whole issue btw, it’s a very nice set of papers). We saw improvement in both languages in semantics and narratives. Some kids demonstrated gains in morphosyntax but others did not. Read the rest of this entry »

Intervention in Two Languages

Posted by Elizabeth D. Peña in between-language, bilingualism, generalizability, narratives, semantics, story grammar, transfer on May 23, 2015

What is the best way to do intervention with bilingual children with LI? It’s not always completely clear. Bilinguals are bilingual because they need both their languages to function in every day activities. With my colleagues, I’ve proposed for a while that in thinking about intervention we need to think about demands that are unique to L1 and L2 and those that are the same. This notion has been illustrated as a Venn diagram to show what overlaps and doesn’t. This figure comes from a chapter in Brian Goldstein’s book (now in it’s 2nd edition) where we postulated the kinds of demands a young child might need to meet in the semantic domain in Spanish vs. English.

Other important questions are what transfers and what doesn’t? We usually want to maximize learning from one language to another. And we often assume that children can and do transfer knowledge from one language to the other. But how does this happen? In particular, how does this happen in children who have language impairment?

I think we can draw on some of the really excellent work that’s been done in bilingual education and in the area of reading. In addition there is emerging work on the topic of intervention with children who have language impairment.

We recently published a new paper in Seminars in Language Disorders, “Dual language intervention for bilinguals at risk for language impairment” by Lugo-Neris, Bedore, and Peña. In this paper 6 bilingual (Spanish-English) children with risk for language impairment participated in an intervention study. Three of the children received intervention in Spanish first for 12 sessions then 12 in English. The other three received intervention in English first, then in Spanish on the same schedule. The interventions focused on semantics, morphosyntax, and story grammar using a book-reading approach.

Testing in both languages was done at baseline and at the end of the study. Results demonstrated that children made gains in both languages on narratives and in Spanish on semantics. Examination of individual changes by first language of intervention shows some interesting patterns. Children who received intervention in Spanish first demonstrated greater gains in both languages in narratives compared to those who received English first intervention. On the other hand, children who received English first demonstrated greater gains in both languages in semantics while those who received Spanish first showed greater gains in Spanish and limited gains in English. So, it seems that the direction of transfer may be mediated by a combination of the target of intervention and the language of intervention. Of course we need to follow up with larger numbers of children to better understand how language of instruction, the child’s language experiences and the language targets together influence the kinds of gains that can be seen. We’re intrigued and excited by these findings and we hope that these will lead to more careful planning of intervention and selecting the language of intervention to maximize between language transfer.

Bilingual intervention: why not?

Posted by Gabriela Simon-Cereijido in child bilingualism, grammar, language impairment, research, vocabulary on April 5, 2014

Bilingualism is finally being understood as what it is: a typical, positive and enriching form of living and of communicating in the United States. That is, an asset rather than a deficit. In many cities, dual language programs are flourishing and parents from multiple backgrounds are showing a commitment to bilingual language and literacy development. This is great news; however, there are still some concerns about bilingual education and bilingual children with language disorders. Are these children able to learn in a dual language classroom? Will they feel overwhelmed and confused? Will they manage to learn English? What should we recommend their parents?

We can now make some recommendations based on recent research conducted with Latino Spanish-speaking preschoolers with language impairment (Gutierrez-Clellen et al., 2012; Restrepo et al., 2013; Simon-Cereijido et al., 2013). And the recommendation is definitely bilingual! We found that the Spanish-speaking children with language disorders learned new English words and increased the length of their English phrases at a faster rate from interventions in Spanish and English, rather than in English only. Moreover, they also showed gains in Spanish.

In a separate study, we collaborated with Head Start teachers who taught our lessons in small groups to bilingual children with and without language impairment (Simon-Cereijido & Gutierrez-Clellen, 2014). All of the children, regardless of ability, made more progress than the bilingual children who did not receive the lessons and who were instructed in English only. Thus, a bilingual approach proved to be more beneficial than an English only approach for the children with language impairment.

This intense vocabulary and oral language intervention was developed following quality preschool evidence-based practices combined with a bilingual approach. Units of four 30-minute lessons were designed around bilingual picture books and every unit introduced the storybook, the new words, and the games in Spanish, the strong language of these children. The children, then, were ready to listen to the same information in English the following day. Days 3 and 4 alternated the languages. We explicitly designed several hands-on activities to repeatedly teach new, less frequent vocabulary (a weakness found in a great number of typical and atypical Latino children). We also designed “Talk and Play” games to facilitate the production of longer utterances. The “Talk and Play” activities used themes from the storybooks, familiar words, and a few toys that would allow the children to take “speaking” risks in a playful environment.

There is still much more to figure out about interventions and programs for bilingual children with language disorders. However, we do know more than before, and we should feel more and more confident to support bilingualism at home and at school.

Gutierrez-Clellen et al., 2012

http://ajslp.pubs.asha.org/article.aspx?articleid=1757528

Restrepo et al., 2013

http://jslhr.pubs.asha.org/article.aspx?articleid=1795805

Simon-Cereijido et al., 2013

http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=9042269&fulltextType=RA&fileId=S0142716412000215

Simon-Cereijido & Gutierrez-Clellen, 2014

http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13670050.2013.866630#.U0Btoqg7s6Y

Bilingual Education Can Benefit All Students

Posted by Elizabeth D. Peña in child bilingualism, ESL, language impairment on September 13, 2010

This is the title of Alexandra Sabater’s post in the Dallas news opinion blog. She writes eloquently about the benefits of bilingual education from her perspective as a teacher. It got me thinking about beliefs about bilingual education for children who have language impairment.

It’s the Wrong Question (Initially): Part 2

Posted by Brian Goldstein in child bilingualism, language impairment, speech sounds on March 30, 2009

In a recent post, I discussed the therapy goal driving the language of intervention and not vice versa. In Part 2, I provide an example focusing on speech sound disorders and some more explanation.

Suppose you determine that a Spanish-English bilingual child has a speech sound disorder in which the trill-sound in Spanish (in a word such as “perro”–dog) and the r-sound (as in “read”) are misarticulated. The goal drives the language of intervention. If you want to remediate the r-sound, you are obligated to do so in English. Only English has that sound-not Spanish. The same is true, of course, for the trill sound in Spanish. You must work on it in Spanish. Clearly, these are somewhat easy cases and easy decisions.

What happens with a sound such as the s-sound, if it is misarticulated in both languages? By the way, if a bilingual child has a disorder, it will occur in both languages, not just in one language (a topic for another post). So, back to the misarticulation of the s-sound in both languages. The goal (and my bias) is to increase the accuracy of that sound in both languages ultimately, but how should this be done? At this point, language of intervention is relevant.

Surprisingly, there are very few studies of treating speech sound disorders in bilingual children (we actually have very few treatment studies in speech-language pathology, but that’s a subject for the future). Such studies include:

Holm, A., & Dodd, B. (2001). Comparison of cross-language generalisation following speech therapy. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica, 53, 166-172.

Holm, A., Ozanne, A., & Dodd, B. (1997). Efficacy of intervention for a bilingual child making articulation and phonological errors. International Journal of Bilingualism, 1, 55-69.

Ray, J. (2002). Treating phonological disorders in a multilingual child: A case study. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 11, 305-315.

Although these studies provide some direction for us, they are all case studies, and thus, we can’t generalize them. That being said, we do need to find some direction. The numerous factors that the students raised (and that were also included in the previous post) come into play: home language, parental choice, use, proficiency, dominance, school language, language of the speech-language pathologist, and availability of interpreters/translators.

You might choose the initial language of intervention based on those, or perhaps other, factors. You might also deliver treatment in one of the following ways:

- English first (or Spanish) to some criterion and then in Spanish (or English) to some criterion

- 1 week in English and 1 in Spanish

- English (or Spanish) for a set number of sessions and then Spanish (or English) for a set number of sessions

At this point, we don’t have research evidence that privileges one approach over the other. However, regardless of which language you start in, it is critical to monitor how that skill is generalized to the other language. If it generalizes, then theoretically you would not have to work on it in the other language. If it does not generalize, however, it would be appropriate to target it in the other language as well. Again, the goal drives the language of intervention with the ultimate outcome of raising a bilingual child who is a competent speaker of both languages.

It’s the Wrong Question (Initially): Part 1

Posted by Brian Goldstein in child bilingualism, language impairment on March 29, 2009

In a recent class on assessment and treatment of diverse populations, we were discussing treating communication disorders in bilingual children by speech-language pathologists. In preparation for this discussion, the students had read papers such as:

Kohnert, K., Yim, D., Nett, K., Kan P.F., Duran, L. (2005). Intervention with linguistically diverse preschool children: A focus on developing home language(s). Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 36, 251-263.

Gutiérrez-Clellen, V. (1999). Language choice in intervention with bilingual children. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 8, 291-302.

Goldstein, B. (2006). Clinical implications of research on language development and disorders in bilingual children. Topics in Language Disorders, 26, 318-334.

I opened the discussion with an open-ended question, “what is the first question you need to ask yourself in planning treatment for bilingual children with communication disorders?” Each and every student said something like, “What language should I treat in?” We then discussed how to make that decision. They raised a number of factors that would be important to know in making that decision such as: home language, parental choice, use, proficiency, dominance, school language, language of the speech-language pathologist, and availability of interpreters/translators. In discussing this topic for almost an hour, we could not agree on exactly how to answer this question. I then told them the truth. There was a reason they couldn’t truly answer the question.

It’s the wrong question (initially). Said another way, it’s the right question but at the wrong time.

I then asked them if the child were monolingual, what would be their first question. They all said, “What’s the goal?” Then why, I asked, is that not the same question for bilinguals? Silence.

Language of intervention is, of course, an important and critical question to answer in working with bilingual children, but I don’t think it’s the first one. Determining the goal drives the language. Language of intervention does not signal the goal.

In a future post, I will provide more detail on this notion and give you an example.