Where to start?

Posted by Elizabeth D. Peña in Uncategorized on March 25, 2024

Do you ever wonder how to decide if a bilingual child has a developmental language disorder (DLD)? We have a new paper here where we outline one approach we developed to identify DLD in bilinguals when there isn’t a gold standard.

Usually, when you develop a new test or approach you compare how well it works against a gold standard. Sensitivity and specificity percentages are how well the new test classifies compared to the gold standard. If the new test is at least 80% accurate in its classification (both sensitivity and specificity), then we say it’s a good test. But, what do we do when there is no gold standard as is often the case when we are testing bilingual kids? Can we use this approach for different language pairs? WHERE DO WE START?

- We started with expert clinicians. Clinicians who were Spanish-English bilinguals, who had several years of clinical experience, who had worked a lot with Spanish-English bilingual kids.

- We looked at the literature. How does English DLD present? How does Spanish DLD present? Where would we see this?

- Our expert clinicians reviewed test, interview and language sample data for 167 kids and made judgements about each of their languages in three domains: narratives, grammar, & semantics.

We made a form, where we asked clinicians to review each case, and to make notes. The included the three domains across the top, and the sources of information (here language samples) along the side.

Clinicians made their notes as they went through the files. We asked them to look at patterns of performance rather than at test scores (see example):

Then, we asked them to provide a rating for each language x domain, and an overall rating, based on their observations of children’s patterns of performance and their knowledge of ESL.

Every 10 cases, the three clinicians discussed the case together and their reasons for their ratings. They re-rated those cases after the discussion. Our findings are that there was high agreement overall in the domain ratings and in the decisions about who had impairment. When there were disagreements, they were usually a 1-point difference. What’s interesting is that even when they paid attention to different things, they were able to make judgements that were consistent with each other.

We then went back to look at the test scores of the kids that were judged to have and not have DLD. And we found large, significant differences on almost all measures of interest. We propose that this might be a good way to structure the data we collect when conducting bilingual assessment. We can then systematically rate each domain to then compare across languages and come up with a rating. We hope to expand this work, and we hope to see what kinds of measures and observations are informative for clinical decision making.

The Bilingual Delay is a MYTH

Posted by Elizabeth D. Peña in assessment, bilingual, bilingualism on December 3, 2023

Last year I had a chance to present this project at Asha, and the paper was published this year in JSLHR. It’s open access so any one can read it! (though when things are behind a paywall and I am an author I am happy to send you a copy, so just ask).

This is a follow up paper to one that is still in development, but we hope to get that one out too. I’ve written about the bilingual delay before, here and here. And my biggest concern about this myth is that often schools, special educators, and yes, SLPs, use this to deny needed services to bilingual children. I so often hear or see comments along the lines of:

- Yes, they do show low skills in both languages, but that’s normal, because of the “bilingual delay.”

- We expect bilingual kids to show delays in both languages, let’s give them more time

- That pattern of low scores in L1 and L2 is what I often see and it’s normal.

THESE ARE ALL MYTHS!!!

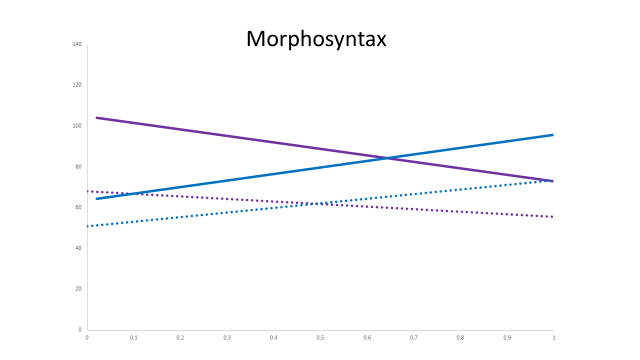

It can APPEAR that bilinguals are delayed if they are tested in only one language. In group studies children who are in the most balanced exposure group (around 50/50 exposure) have lower scores than their more monolingual counterparts. But, these are based on AVERAGES. What happens if we look at scores at the individual level? That’s what we did. Here are scores for 600 bilingual Spanish-English speaking US children. The solid lines represent 500 typical kids, and the dotted lines represent 100 kids with DLD. These are all standard scores with a mean of 100 and a SD of 15. You can see that the Spanish scores (in purple) go down as they have more exposure to English; and the English scores (in blue) go up. So, yes, it does look like the kids in the middle (who have more balanced exposure) are low in both.

But, let’s look at individual scores. Here, we show the English and Spanish scores for kids who have more than 90% exposure to English (blue bar). You can see that all but one score better in English. We see the same general pattern for Spanish (pink bar) most of the kids with a lot of Spanish exposure do better in Spanish. What about the kids in the middle– the yellow bar. Well, it’s 50/50! Some kids do better in Spanish and some do better in English!

So, we then went back to the data and graphed the kids again. This time in their best language only. So, if their score was higher in English, we put in that score into the graph, and if it was higher in Spanish we entered that score. Here are the results. The lines are essentially straight. And there are no significant differences associated with exposure to language. For typical kids, the average scores are right at 100 across the board. And for kids with DLD, their scores average around 60, again across the board. So, I would expect a typical child to show scores in the normal range in at least one of their languages. Kids with DLD will show low scores in both. And notice, that their better scores are within the same range as more monolingual kids, so again they can handle bilingualism.

So, please stop perpetuating myths. There is no such thing as a bilingual delay. We included kids with early exposure and late exposure to two languages, and kids with the whole range of current exposure. There is no bilingual delay.

Monolingualism is not a cure for DLD

Posted by Elizabeth D. Peña in assessment, between-language, bilingual, child bilingualism, developmental language disorder on November 7, 2023

So, this is about the 5th time that this question has come up in the last 7 days! And it’s variations of:

- Wouldn’t it be better for a bilingual child with DLD to be in English only?

- But, language is so hard, isn’t bilingualism harder for children with DLD?

- Would we see more progress if we focused only on one language?

The answer to this and other variants of the question is NO!

NO, NO NO NO NO NO!

I don’t think I can say it enough. And what’s infuriating about this is that it’s usually someone who, hasn’t studied bilingualism, or isn’t bilingual (often both), and they can’t just accept that it’s not the way to go. They pose more scenarios (not based on their expertise or the literature, or on much of anything, but on their own intuition).

But, the research is pretty clear. Doing intervention in two languages doesn’t slow down acquisition of English. Bilingual education, doesn’t slow down English language learning. Kids with DLD who are bilingual struggle not because of bilingualism but because of their DLD. Language is hard– one language is hard, two languages are hard. But (and here’s the point) if you NEED two languages to communicate, to connect with the people in your life, you need two languages. And it won’t slow you down any more than DLD will. And it gives you more people to talk to and that’s a good thing.

Research? Yes, Plenty of it!

Here’s a new paper that’s very cool– this was a group of young children with Down syndrome. Researchers looked at the amount of exposure they had to Welsh and English. They found that their English growth was not affected by exposure to Welsh.

Here’s another paper that I was the lead on. We studied just under 600 Spanish-English bilinguals; 100 with DLD at different levels of exposure to English and Spanish. We found that if we looked at kids in their better language (at the individual level) there were no effects of exposure to the other language. This was true for DLD and typical groups. The kids with DLD scored lower on morphosyntax and semantics measures than the typical kids– as expected. But, they did not score lower than their monolingual counterparts with DLD (and just think, they can talk to more people).

In an another paper found here, we tested about 1000 bilingual kids. We looked at how many kids fell into the lowest quartile of performance indicating risk for DLD. Comparing by level of exposure there were no differences by group, so we concluded that bilingualism does not pose an added risk for poor performance (when you test in both languages). In fact the group that had been bilingual the longest had a tiny bit LESS risk. Bilingualism is good for you.

In this paper, researchers found that a monolingual English vocabulary intervention vs. a bilingual (Spanish-English) vocabulary intervention resulted in no posttest differences for English. Though the bilingual vocabulary intervention also supported Spanish.

There are more papers, and many of them are in this blog– look around. But, stop it with this nonsense. Please!

Intervention in Spanish leads to gains in Spanish & English

Posted by Elizabeth D. Peña in between-language, bilingual, intervention on August 15, 2022

My colleagues and I have completed a series of studies looking at whether we can promote between-language transfer and how much the language of intervention matters. In a couple of studies, we’ve compared language of instruction assigning bilinguals to either Spanish or English intervention conditions and in one study we assigned children to Spanish or English then switched language of intervention halfway through. We see evidence of between language transfer in these conditions.

In another two-part (working on part three) series we’ve been interested in whether doing intervention in the child’s home language (Spanish) leads to gains in Spanish or both Spanish and English. In one study, we looked at grammatical interventions and I talked about that last time I posted. We used broad principles of learning to plan for between-language grammatical transfer so that we could maximize impact between the two languages. You can read that paper here.

What about semantics and narratives? Our intervention was a book-based intervention where we worked on building semantic networks related to the books’ themes. We used target words to build children’s verb and noun phrases. And we used principles of mediated learning to teach children about story structure, characters, settings, actions, and resolutions.

We looked at three measures for this, a single-word vocabulary test (EOWPVT-SBE), a semantics test (BESA), and a narrative test (TNL) administered in Spanish and English. Our results demonstrate gains on the narrative and semantic tasks. While gains were greater in Spanish (between 1 and 1.3 SD), which was the language of instruction, we also saw significant gains in English (between .3 and .67 SD).

What were the elements? We leveraged meaning and tried to target concepts that could transfer. In the semantics domain, about 1/3 of the words we selected were Spanish-English cognates. We focused on strategies to help children make connections among words and word meanings using semantic maps, definitions, and making connections between what they already knew, wanted to know, and what they learned (KWL). For the narrative intervention portion, we targeted story elements, used a book-walk approach, and supported story predictions.

This is a small study, with only 13 children, but we are adding to the knowledge base around bilingual interventions and ways we can better support between-language transfer.

Designing Intervention for Between-Language Transfer

Posted by Elizabeth D. Peña in between-language, bilingual, developmental language disorder, intervention on January 4, 2022

SLPs working with bilingual children often ask how to design interventions that promote transfer. We know that it’s not appropriate to take away a child’s home language. We also know that most SLPs (95% or more) only speak one language. So what do we do?

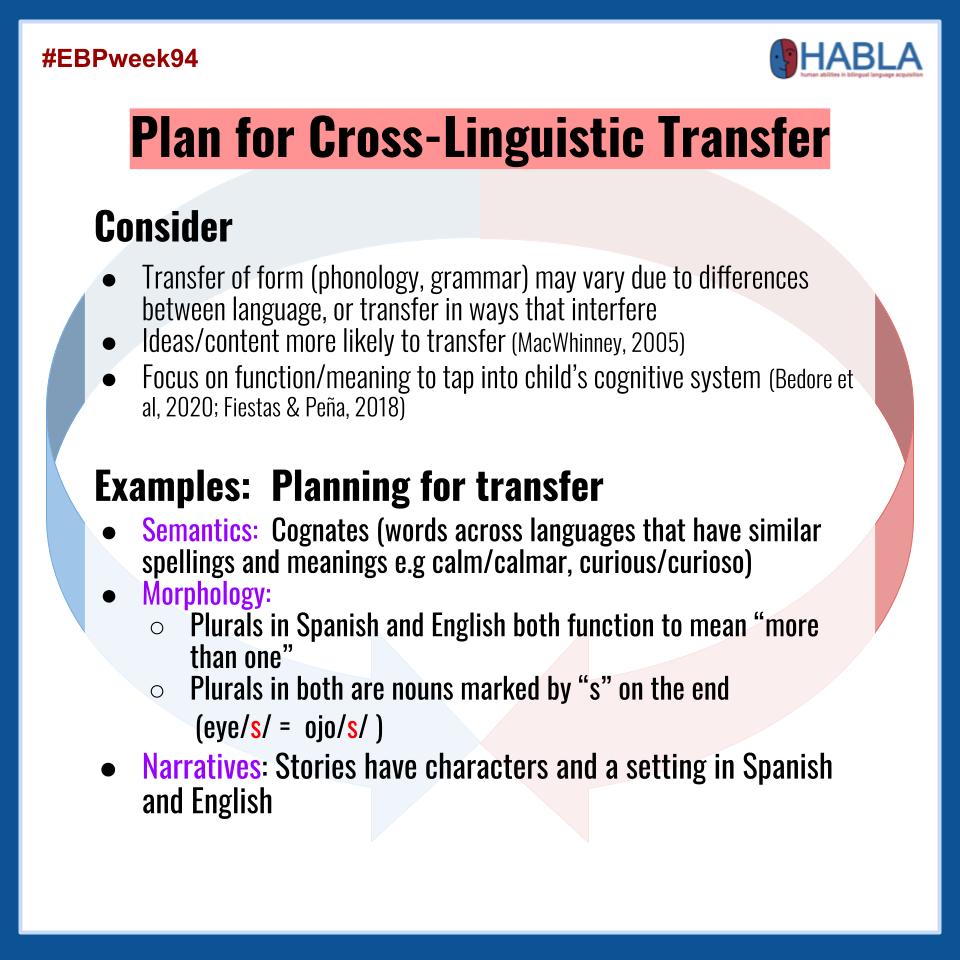

This is a question that my colleagues and I have thought about a lot. I’ve written about our previous studies here and here. We know that not everything transfers. Some parts of language seem to more readily transfer between languages. Usually meaning including story structure, vocabulary and semantics. But form doesn’t transfer as easily. If forms are shared– plural s in Spanish and English for example, they are more likely to transfer. But, it’s less likely that the subjunctive form in Spanish will transfer to English. They are too different.

Still, we wanted to incorporate grammatical goals into our intervention since grammar is an area of difficulty for children with DLD. First, we thought about broad principles of language learning that would support transfer. We drew from MacWhinney’s Unified Model to help us think about transfer:

- Resonance helps to reinforce patterns. We made sure that the vocabulary we used was drawn from the curriculum, and that we used the vocabulary in full phrases and sentences. We reasoned that this would help children learn the grammatical patterns as well as the vocabulary.

- Proceduralization helps children make connections. Rather than teaching grammatical forms in isolation we emphasized features in larger story telling contexts using repeated exposures.

- Internalization is the process by which children may regulate their own actions through language. We expand this by supporting children’s use of L1 in supporting metalinguistic awareness. We propose that this self-talk in the L1 can help form a bridge between L1 and L2 learning.

- Transfer can be negative or positive. In negative transfer, children might incorrectly apply patterns for their L1 to the L2. In positive transfer they might use what they know to leverage use of forms in L2. We tried to promote positive transfer through use of cognates, and through pointing out similarities (and differences) in the grammars of the two languages.

Grammatical Target Selection

In our study, we did not individualize targets for each child. Instead, we identified the kinds of targets that are most difficult for children with DLD in Spanish and in English. We wanted to provide support for grammatical comprehension and production within narrative and expository texts. What’s seems to be difficult for children with DLD is forms that are less salient in the input. We identified constructions at a broad level that are difficult for children with DLD in both Spanish and English and also how they might manifest differently across the two languages. We thought about effective communication through elaboration and precision. Targets we chose included the following:

- Elaborated noun phrases are the building blocks for grammar across both languages. And we could build up the vocabulary words they were learning into these descriptive phases. We included use of prepositions and adjectives. In Spanish, we made sure to focus on number and gender agreement in using adjectives + nouns since this is an area of difficulty for kids with DLD.

- Tense and complex utterances were targeted to help support expression of causal and temporal relationships within the stories that children hear, read, and told.

- Deictic reference – we incorporated use of articles and pronouns from the texts to emphasize different points of view, references, and agreement.

Results indicated significant gains across grammatical forms in Spanish including (clitics, subjunctive, imperfect, and adjective agreement). There were also significant gains in English (even though the intervention was completely in Spanish). Gains we noted in English included 3rd singular, passives, and negatives. We think that through an approach which emphasized expression of complete and elaborated ideas, children started paying more attention to ways they could be more precise in their use of grammar. Thus, in this study, it wasn’t about the specific forms but rather providing the tools (and models) that children could use to express their knowledge through language. The focus wasn’t as much on the “correctness” of use but on elaboration and expression of meaning. And this could be done across both languages.

This is just a small study, but it gives us a glimpse into how we can use these learning principles with broad grammatical targets to support transfer. If you want to read the original paper, you can do so here.

How nonverbal are nonverbal IQ tasks?

Posted by Elizabeth D. Peña in assessment, bilingual, bilingualism, child bilingualism, child language impairment, culture on December 13, 2021

I think we sometimes ASSUME that nonverbal tasks are nonverbal in the same way. And you know what happens when we assume right?? This is true for IQ tests that test nonverbal abilities. We have to ask what kinds of abilities? How are these tested? How are they elicited? And, how are they observed?

There are different kinds of nonverbal tasks. Sometimes the instructions are given verbally but the response is pointing, manipulating, constructing, or gesturing. Sometimes both instructions and responses are nonverbal. Some IQ tests are fully nonverbal, others have nonverbal subtests. In a paper published a couple of years ago, we were interested in how bilingual children with and without developmental language disorder (DLD) performed on nonverbal tests.

Read the rest of this entry »Test Reviews

Posted by Elizabeth D. Peña in Uncategorized on September 1, 2021

I teach psychometrics and measurement– now at the Ph.D. level at UCI. Previously at the MA level at UT. And I’ve often talked about how to select tests for diagnostic decision making. We want to select measures that do the job! For making a decision about whether someone has an impairment or not, we need to use procedures that have good sensitivity and specificity. Validity and reliability is good, but not enough.

I used to have an assignment in my class for MA students where they had to select a set of measures for a fictional speech and language clinic, given a budget. They had to review and justify their purchases, covering the target age range, possible needs and disorder categories. Importantly, they needed to select measures that did the job. I figured they would leave with a good list of possible measures that work (easy b/c MOST DON’T!!). From time to time, someone will ask me for the list of tests and I hunt it down and send it out. I finally decided to make it easy on myself and to make the list into a viewable google sheet. The bolded measures are those that report sensitiity and specificity of at least 80%. These are the ones that do the job. I also know that there are newer and updated measures, and new information on old measures. If you want to help update the list, here’s a form you can complete. It will automatically update in the google sheet under the new measures tab.

Bilingual SLP or SLP who is bilingual?

Posted by Elizabeth D. Peña in bilingual, bilingualism on January 27, 2021

There’s a difference.

Every so often, I see a question about whether someone who is bilingual should bother to complete a bilingual specialization or certificate program as part of their graduate training. The answers vary, and certainly there aren’t enough bilingual MA or MS programs that can provide the training, but does it matter. For me, it does. I think that SLPs who consider themselves bilingual SLPs have an ethical responsibility to be on top of the knowledge base required to practice in this area. Just like any SLP who is hired into any other position needs to have the knowledge base to meet the demands of that position.

A bilingual SLP needs to have knowledge and skills regarding bilingual development, identification of disorder in bilinguals, bilingual treatment, and knowledge about cultural factors that may impact service delivery. Asha has a statement outlining the baseline knoweldge you need to have to call yourself a bilingual SLP. Knowing another language alone does not provide you with this knowledge base any more than knowing English by itself would make you an SLP– SLPs have to complete an MA or MS degree taking courses that cover the scope of practice in the different disorder categories. I can’t imagine for example, that an SLP who stutters for example would be able to skip learning about how to assess and treat stuttering. Yes, they would bring in insights that others might not have, but it wouldn’t prepare them to work with this population. The difference of course is that knowledge and skills in bilingual assessment and treatment across all the disorder areas is not required for graduation, licensure or certification at a national level. Yet, I think that if we are going to serve bilingual populations, we need to develop the knowledge base to do so. Being bilingual IS NOT ENOUGH.

If you are bilingual and an SLP and don’t know about bilingual development, disorders, assessment, intervention, and counseling, then you are an SLP who is bilingual. You can become a bilingual SLP but you are not one yet. If this is the case, then taking courses, CEUs, reading the literature is a good way to develop and expand your practice.

Asha does not have specific rules for certifying that bilingual SLPs actually have the knowledge base that they claim. We must rely on each individual’s ethics in appropriately representing their skills and competencies. If you claim to be a bilingual SLP you are claiming that you have expertise in bilingualism, including bilingual assessment and treatment.

Children’s use of Spanish in the U.S. Context

Posted by Elizabeth D. Peña in bilingual, bilingualism, child bilingualism, morphosyntax on December 31, 2020

In this paper, we studied Spanish-English bilinguals between the ages of 4 and 7 years old. We were interested in the relationship between bilingual children’s age, their productivity in Spanish (as indexed by MLU) and their accuracy in morpheme production. We found that age didn’t predict correct production of grammatical forms but MLU did. The grammatical forms that children demonstrated mastery on (80% or more accurate) was related to MLU. We also found that relative difficulty for grammatical forms was similar for different levels of Spanish fluency. Let’s break it down.

Here you can see what forms children produced accurately (80% or more correct) as related to their MLU.

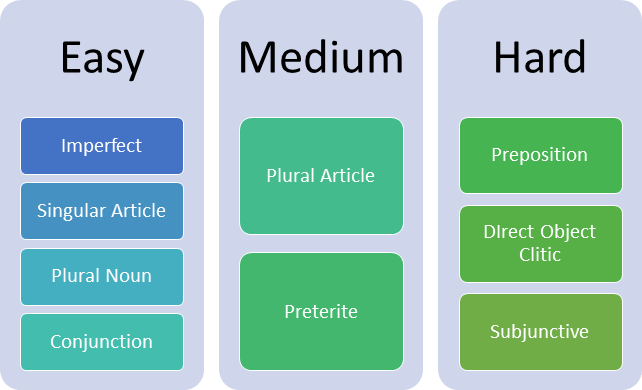

This graphic shows the relative difficulty in children’s productives of these forms. These are based on averages from 228 Spanish-English bilingual children between the ages of 4 and 7. Easy forms are those that children on average produced correctly about 70% or more of the time. Medium forms are those children produced correctly about 60% of the time. Finally, the hard items are those that children produced correctly about 40-50% of the time.

I hope that this information is useful for those who work with Spanish-English speaking children.