Archive for category bilingualism

The Bilingual Delay is a MYTH

Posted by Elizabeth D. Peña in assessment, bilingual, bilingualism on December 3, 2023

Last year I had a chance to present this project at Asha, and the paper was published this year in JSLHR. It’s open access so any one can read it! (though when things are behind a paywall and I am an author I am happy to send you a copy, so just ask).

This is a follow up paper to one that is still in development, but we hope to get that one out too. I’ve written about the bilingual delay before, here and here. And my biggest concern about this myth is that often schools, special educators, and yes, SLPs, use this to deny needed services to bilingual children. I so often hear or see comments along the lines of:

- Yes, they do show low skills in both languages, but that’s normal, because of the “bilingual delay.”

- We expect bilingual kids to show delays in both languages, let’s give them more time

- That pattern of low scores in L1 and L2 is what I often see and it’s normal.

THESE ARE ALL MYTHS!!!

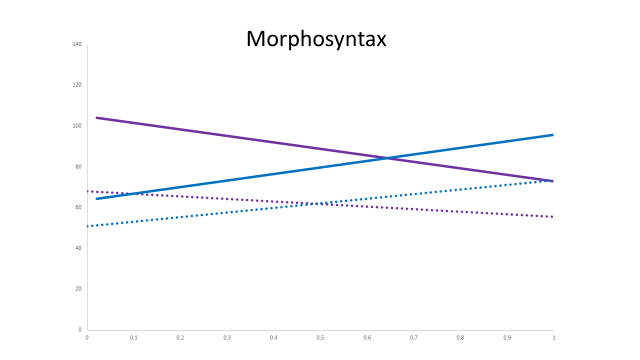

It can APPEAR that bilinguals are delayed if they are tested in only one language. In group studies children who are in the most balanced exposure group (around 50/50 exposure) have lower scores than their more monolingual counterparts. But, these are based on AVERAGES. What happens if we look at scores at the individual level? That’s what we did. Here are scores for 600 bilingual Spanish-English speaking US children. The solid lines represent 500 typical kids, and the dotted lines represent 100 kids with DLD. These are all standard scores with a mean of 100 and a SD of 15. You can see that the Spanish scores (in purple) go down as they have more exposure to English; and the English scores (in blue) go up. So, yes, it does look like the kids in the middle (who have more balanced exposure) are low in both.

But, let’s look at individual scores. Here, we show the English and Spanish scores for kids who have more than 90% exposure to English (blue bar). You can see that all but one score better in English. We see the same general pattern for Spanish (pink bar) most of the kids with a lot of Spanish exposure do better in Spanish. What about the kids in the middle– the yellow bar. Well, it’s 50/50! Some kids do better in Spanish and some do better in English!

So, we then went back to the data and graphed the kids again. This time in their best language only. So, if their score was higher in English, we put in that score into the graph, and if it was higher in Spanish we entered that score. Here are the results. The lines are essentially straight. And there are no significant differences associated with exposure to language. For typical kids, the average scores are right at 100 across the board. And for kids with DLD, their scores average around 60, again across the board. So, I would expect a typical child to show scores in the normal range in at least one of their languages. Kids with DLD will show low scores in both. And notice, that their better scores are within the same range as more monolingual kids, so again they can handle bilingualism.

So, please stop perpetuating myths. There is no such thing as a bilingual delay. We included kids with early exposure and late exposure to two languages, and kids with the whole range of current exposure. There is no bilingual delay.

How nonverbal are nonverbal IQ tasks?

Posted by Elizabeth D. Peña in assessment, bilingual, bilingualism, child bilingualism, child language impairment, culture on December 13, 2021

I think we sometimes ASSUME that nonverbal tasks are nonverbal in the same way. And you know what happens when we assume right?? This is true for IQ tests that test nonverbal abilities. We have to ask what kinds of abilities? How are these tested? How are they elicited? And, how are they observed?

There are different kinds of nonverbal tasks. Sometimes the instructions are given verbally but the response is pointing, manipulating, constructing, or gesturing. Sometimes both instructions and responses are nonverbal. Some IQ tests are fully nonverbal, others have nonverbal subtests. In a paper published a couple of years ago, we were interested in how bilingual children with and without developmental language disorder (DLD) performed on nonverbal tests.

Read the rest of this entry »Bilingual SLP or SLP who is bilingual?

Posted by Elizabeth D. Peña in bilingual, bilingualism on January 27, 2021

There’s a difference.

Every so often, I see a question about whether someone who is bilingual should bother to complete a bilingual specialization or certificate program as part of their graduate training. The answers vary, and certainly there aren’t enough bilingual MA or MS programs that can provide the training, but does it matter. For me, it does. I think that SLPs who consider themselves bilingual SLPs have an ethical responsibility to be on top of the knowledge base required to practice in this area. Just like any SLP who is hired into any other position needs to have the knowledge base to meet the demands of that position.

A bilingual SLP needs to have knowledge and skills regarding bilingual development, identification of disorder in bilinguals, bilingual treatment, and knowledge about cultural factors that may impact service delivery. Asha has a statement outlining the baseline knoweldge you need to have to call yourself a bilingual SLP. Knowing another language alone does not provide you with this knowledge base any more than knowing English by itself would make you an SLP– SLPs have to complete an MA or MS degree taking courses that cover the scope of practice in the different disorder categories. I can’t imagine for example, that an SLP who stutters for example would be able to skip learning about how to assess and treat stuttering. Yes, they would bring in insights that others might not have, but it wouldn’t prepare them to work with this population. The difference of course is that knowledge and skills in bilingual assessment and treatment across all the disorder areas is not required for graduation, licensure or certification at a national level. Yet, I think that if we are going to serve bilingual populations, we need to develop the knowledge base to do so. Being bilingual IS NOT ENOUGH.

If you are bilingual and an SLP and don’t know about bilingual development, disorders, assessment, intervention, and counseling, then you are an SLP who is bilingual. You can become a bilingual SLP but you are not one yet. If this is the case, then taking courses, CEUs, reading the literature is a good way to develop and expand your practice.

Asha does not have specific rules for certifying that bilingual SLPs actually have the knowledge base that they claim. We must rely on each individual’s ethics in appropriately representing their skills and competencies. If you claim to be a bilingual SLP you are claiming that you have expertise in bilingualism, including bilingual assessment and treatment.

Children’s use of Spanish in the U.S. Context

Posted by Elizabeth D. Peña in bilingual, bilingualism, child bilingualism, morphosyntax on December 31, 2020

In this paper, we studied Spanish-English bilinguals between the ages of 4 and 7 years old. We were interested in the relationship between bilingual children’s age, their productivity in Spanish (as indexed by MLU) and their accuracy in morpheme production. We found that age didn’t predict correct production of grammatical forms but MLU did. The grammatical forms that children demonstrated mastery on (80% or more accurate) was related to MLU. We also found that relative difficulty for grammatical forms was similar for different levels of Spanish fluency. Let’s break it down.

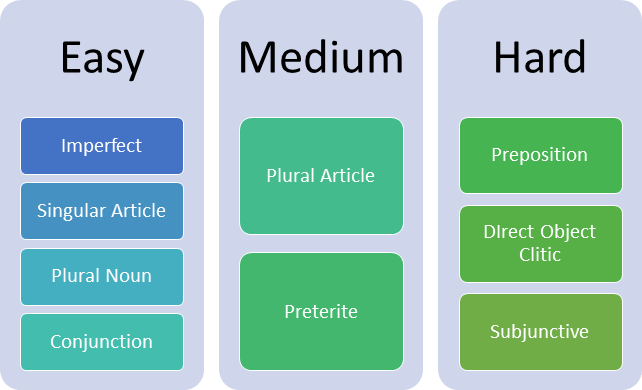

Here you can see what forms children produced accurately (80% or more correct) as related to their MLU.

This graphic shows the relative difficulty in children’s productives of these forms. These are based on averages from 228 Spanish-English bilingual children between the ages of 4 and 7. Easy forms are those that children on average produced correctly about 70% or more of the time. Medium forms are those children produced correctly about 60% of the time. Finally, the hard items are those that children produced correctly about 40-50% of the time.

I hope that this information is useful for those who work with Spanish-English speaking children.

Why Opinion and Personal Observation isn’t as good as Systematic Research

Posted by Elizabeth D. Peña in assessment, bilingual, bilingualism, child bilingualism, child language impairment, developmental language disorder, Uncategorized on April 17, 2020

Families of bilingual children with developmental language disorder (DLD) are often told to use only one language. School district personnel may insist that these children receive instruction in only one language even if there are bilingual programs available. Even bilingual personnel who work with children (teachers and SLPs for example) may say that children with DLD can become more confused if in a bilingual environment. This is simply not true. I have participated in many studies that demonstrate that bilingual children are not more likely to show higher risk for DLD than monolinguals; we know that bilingual children with DLD show comparable performance to monolingual children with DLD; we know that bilingual children with DLD show cognate advantages similar to typical bilinguals; we know that intervention in one language can carry over to the other language. This work is all supported by the data-based research (linked) and is consistent with work that other researchers are doing. Read the rest of this entry »

Testing in Two Languages

Posted by Elizabeth D. Peña in between-language, bilingual, bilingualism, child bilingualism, semantics, vocabulary on May 2, 2019

When we test bilingual children we need to be able to do so in both of their languages. We can to look at speech and language in each of their two languages and we use this information to determine if their language production is like that of their typical (bilingual peers).

In the area of lexical-semantics we know that children who have exposure to two languages often show patterns of lexical knowledge consistent with their divided exposure. They may know home words in the home language and school words in the second language. It makes it difficult to test in only one language, but how do we take account of both their languages?

One of the observations we’ve made in many years of testing bilingual kids is that it is difficult at times for them to switch between languages– especially when they’ve been using English in diagnostics. This doesn’t mean of course that kids don’t codeswitch, they do and they do so during testing, but switching between languages on demand is hard.

Cognate Advantage in DLD

Posted by Elizabeth D. Peña in between-language, bilingual, bilingualism, child bilingualism, child language impairment, developmental language disorder, English, language impairment, semantics, Spanish, vocabulary on April 15, 2019

Cognates are really interesting words that share meaning and sound the same across languages. Languages that share the same roots also have a large number of cognates because of their shared histories. Spanish and English share a large number of cognates.

We’ve studied cognate recognition in young children. In that study of kindergarten and first grade children, we found that Spanish dominant children and English dominant children scored similarly on a receptive vocabulary test given in English. But, they showed different patterns of response. Those who were Spanish dominant were more likely to know the cognates– even those that were above their age level. English dominant kids tended to know non-cognates. So, consistent with other studies, we found a cognate advantage for Spanish-speaking children learning English as a second language. In a recent study, we were interested in whether bilingual children with DLD would show a similar cognate advantage. Read the rest of this entry »

Stop Telling Parents of Bilingual Children to Use One Language

Posted by Elizabeth D. Peña in bilingual, bilingualism, child bilingualism, child language impairment on September 18, 2018

I keep hearing these stories and it’s infuriating! There’s no evidence that bilingualism is confusing and no evidence that bilingualism makes developmental language disorder worse so stop it! Read the rest of this entry »

Can we improve home language surveys?

Posted by Elizabeth D. Peña in assessment, between-language, bilingual, bilingualism, child bilingualism on September 10, 2018

I’m working on a paper that focuses on language dominance, proficiency and exposure. I’ve written about these definitions before. Here, I want to think about how it is we capture this information.

There are a number of really nice surveys and questionnaires that have been developed that help to document this information. These include L1 and L2 age of acquisition; educational history in each language, rating of proficiency in each language. Sometimes this is broken out into speaking, listening, reading and writing. Some questionnaires ask about what language is more proficient, and may ask for what purpose(s) each language is used. This information is designed to get at the question of how language is used and how proficient an individual might be across situations. Read the rest of this entry »

What should you expect in the two languages of US Mandarin-English bilingual children?

Posted by Ying Hao in bilingualism, child bilingualism, culture, narratives on August 15, 2018

If you are a speech-language pathologist, have you noticed that in recent years there has been some Mandarin-speaking children on your patient list? If you are a parent of a Mandarin-English bilingual child, do you at times worry about your child’s language development? Both of you may wonder: what does a typical language profile look like for US Mandarin-English bilingual children? It may be hard for you to find relevant studies, but luckily we have just published some data to address this question.

We had 21 Mandarin-English bilingual children from the central Texas. Mandarin was their first language as both parents were Mandarin-speaking, and they started learning English later when they started school. We presented a wordless picture book to children and asked them to tell us a complete story. We asked them to tell stories in both languages: Mandarin and English.

In order to tell stories, these children, who were around 7 years old, had to use their all their language skill. This was not an easy task for a child who just entered school because they may not be fluent in one of their languages depending on when they started learning English and whether they used Mandarin at home. The stories really provided us a way to describe children’s language performance. We looked at macrostructure – the global structure of a story. For example, whether the child included main characters in the story, whether there was an event that initiated the story, whether the development and the consequence of the event were stated, and whether the characters had any internal responses corresponding to the event.

We also examined what specific linguistic features were used in each language – microstructure. As you may know, Mandarin and English are very different. One big difference is that English uses affixes (e.g., plural –s, past tense –ed), whereas Mandarin does not. Mandarin has a classifier inserted between a number and a noun when people count objects (e.g., san ZHI qingwa – three ZHI frogs), but English does not. There are many other differences and these are just some examples. In each language, we selected 17 features to present children’s overall microstructure in that language.

Then we compared children’s performance between the two languages on macrostructure and microstructure. We knew that these children at the time of testing listened to and spoke more English than Mandarin daily, so we considered experience in our data computation. After statistically accounting for current language experience, we found that macrostructure was comparable between the two languages. That says if children know that they need to include these key elements into a story, they can do it in both languages. However, we saw a big difference in microstructure, with English significantly better than Mandarin. Children could easily produce many English features, but could not produce most Mandarin features.

Does this relate to their imbalanced cumulative language experience in English and Mandarin? The answer is YES. Age, associated with cumulative language exposure, was only related to macro- and microstructure in English but not Mandarin. Probably, to maintain Mandarin as a heritage language, these bilingual children needed to gain more exposure and to practice Mandarin more often. Another thing we considered was that increased English experience may interfere the growth of Mandarin, as the two languages are typologically distinct.

A caveat I would like to note is that these children were from Texas, and we did not know if these results could apply to children living in other places where Mandarin has stronger community support for use (like New York, California……). We will strive to find the answers for you in our future studies.

If you want to read the publication, here is the link: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323641964_Narrative_skills_in_two_languages_of_Mandarin-English_bilingual_children